Paradise Lost

| Paradise Lost | |

|---|---|

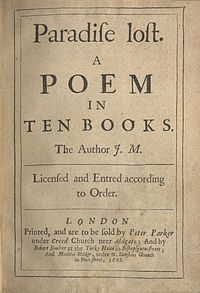

Title page of the first edition (1668) | |

| Author | John Milton |

| Country | England |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Epic poem |

| Publisher | Samuel Simmons (original) |

| Publication date | 1667 |

| Media type | |

| Followed by | Paradise Regained |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

The poem concerns the Christian story of the Fall of Man: the temptation of Adam and Eve by the fallen angel Satan and their expulsion from the Garden of Eden. Milton's purpose, stated in Book I, is to "justify the ways of God to men"[2] and elucidate the conflict between God's eternal foresight and free will.

Milton incorporates Paganism, classical Greek references, and Christianity within the poem. It deals with diverse topics from marriage, politics (Milton was politically active during the time of the English Civil War), and monarchy, and grapples with many difficult theological issues, including fate, predestination, the Trinity, and the introduction of sin and death into the world, as well as angels, fallen angels, Satan, and the war in heaven. Milton draws on his knowledge of languages, and diverse sources – primarily Genesis, much of the New Testament, the deuterocanonical Book of Enoch, and other parts of the Old Testament. Milton's epic is generally considered one of the greatest literary works in the English language.

Contents[show] |

[edit] Synopsis

The story is separated into twelve books, broken down shortly after initial publication, following the model of the Aeneid of Virgil. The books' lengths vary; longest being Book IX, with 1,189 lines, and the shortest Book VII, having 640. In the second edition, each book was preceded by a summary titled "The Argument". The poem follows the epic tradition of starting in medias res (Latin for in the midst of things), the background story being told in Books V-VI.Milton's story contains two arcs: one of Satan (Lucifer) and another of Adam and Eve. The story of Satan follows the epic convention of large-scale warfare. It begins after Satan and the other rebel angels have been defeated and cast by God into Hell, or as it is also called in the poem, Tartarus. In Pandæmonium, Satan employs his rhetorical skill to organize his followers; he is aided by his lieutenants Mammon and Beelzebub. Belial and Moloch are also present. At the end of the debate, Satan volunteers himself to poison the newly created Earth. He braves the dangers of the Abyss alone in a manner reminiscent of Odysseus or Aeneas.

The story of Adam and Eve's temptation and fall is a fundamentally different, new kind of epic: a domestic one. Adam and Eve are presented for the first time in Christian literature as having a full relationship while still without sin. They have passions and distinct personalities. Satan successfully tempts Eve by preying on her vanity and tricking her with rhetoric, and Adam, seeing Eve has sinned, knowingly commits the same sin. He declares to Eve that since she was made from his flesh, they are bound to one another so that if she dies, he must also die. In this manner Milton portrays Adam as a heroic figure, but also as a deeper sinner than Eve, as he is aware that what he is doing is wrong.

After eating the fruit, Adam and Eve have lustful sex, and at first, Adam is convinced that Eve was right in thinking that eating the fruit would be beneficial. However, they soon fall asleep, having terrible nightmares, and after they awake, they experience guilt and shame for the first time. Realizing that they have committed a terrible act against God, they engage in mutual recrimination.

However, Eve's pleas to Adam reconcile them somewhat. Her encouragement enables Adam and Eve both to approach God, to "bow and sue for grace with suppliant knee," and to receive grace from God. Adam goes on a vision journey with an angel where he witnesses the errors of man and the Great Flood, and is saddened by the sin that they have released through consumption of the fruit. However, he is also shown hope—the possibility of redemption—through a vision of Jesus Christ. They are then cast out of Eden and the archangel Michael says that Adam may find "A paradise within thee, happier far." They now have a more distant relationship with God, who is omnipresent but invisible (unlike the previous, tangible, Father in the Garden of Eden).

[edit] Characters

Satan: Satan is the first major character introduced in the poem. A beautiful youth, he is a tragic figure best described by his own words "Better to reign in Hell than serve in Heaven". He is introduced to Hell after a failed rebellion to wrestle control of Heaven from God. Satan's desire to rebel against his creator stems from his unwillingness to accept that all beings don't deserve freedom, declaring the angels "self-begot, self-raised",[3] thereby eliminating God’s authority over them as their creator.Satan is portrayed as charismatic and persuasive. Satan's persuasive powers are first evident when he makes arguments to his angel-followers as to why they should try to overthrow God. He argues that they ought to have equal rights to God and that Heaven is an unfair monarchy, stating, "Who can in reason then or right assume/ Monarchy over such as live by right/ His equals, if in power and splendor less / In freedom equal? or can introduce/ Law and edict on us, who without law/ Err not, much less for this to be our Lord,/ And look for adoration to th' abuse/ Of those imperial titles which assert/ Our being ordained to govern, not to serve?."[4]

Satan's persuasive powers are also evident during the scene in which he assumes the body of a snake in order to convince Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. First, he wins Eve's trust by giving her endless compliments. And when she is perplexed (and impressed) by a "serpent" that is able to talk, Satan tells her that he gained the ability to talk by eating from the Tree of Knowledge and argues that if she were to also eat from the Tree, she would become god-like. He convinces her that the fruit will not kill her and that God will not be upset with her if she eats from the tree. Like his argument to his followers, Satan also argues against God's omnipotence, stating "Why then was [eating from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil] forbid? Why but to awe,/ Why but to keep ye low and ignorant, / [God's] worshippers; he knows that in the day/ Ye eat thereof, your eyes that seem so clear,/ Yet are but dim, shall perfectly be then/ Opened and cleared, and ye shall be as gods./ So ye shall die perhaps, by putting off/ Human, to put on gods."[5]

Satan is narcissistic to the point of solipsism. His ego is both his greatest strength as it motivates him to succeed but also his greatest weakness. He is continually outdone by his own overconfidence. Satan's pathological vanity is shown by the fact that he is actually aroused by his own image. Upon observing that Sin resembles a female version of himelf, he feels sexual attraction to her (before finding out that she is his daughter). Milton's Satan feels guilt and doubt before he tricks Eve, knowing the results of his actions will curse innocents. Similarly, Satan has feelings of guilt when he first enters Paradise. But his feelings always turn to re-affirmation once he reflects on his own exile from Heaven.

The role of Satan as a driving force in the poem has been the subject of much scholarly debate. Positions range from views of William Blake who stated Milton "wrote in fetters when [he] wrote of Angels and God, and at liberty when of Devils and Hell, [because] he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it"[6] to critic William H. Marshall's interpretation of the poem as a Christian morality tale.[7]

Adam: Adam is the first human in Eden created by God. He is more intelligent than Eve and is also stronger, not only physically but morally. From the questions he asks the angel Raphael, it is clear that Adam has a deep, intellectual curiosity about his existence, God, Heaven, and the nature of the world. This is a kind of curiosity that Eve does not have.

As in the Bible, Eve is subservient to Adam, but in Milton's version of the story, Adam is rather easily manipulated by Eve's charms and good looks. Adam, in Milton's version of the character, is worshipful of Eve, partially because of her great beauty, and at times, is subservient to her wishes. His fall will result from this excessive and almost submissive love to his wife, namely his "uxoriousness". Hence, the power dynamic between Adam and Eve is more complicated than the one that is established in the Bible.

Adam also feels a noble sense of responsibility towards Eve (since she was, after all, created from his rib), and he fears for her safety, especially after hearing from the angel Raphael of Satan's infiltration of Paradise.

As opposed to the Biblical Adam, this version of Adam is given a glimpse of the future of mankind (this includes a synopsis of stories from The Old and New Testaments), by the angel Michael, before he has to leave Paradise.

She is extremely beautiful, and her beauty not only obsesses Adam but also herself. After she is born, she gazes at her reflection in a pool of water, transfixed by her image. Even after Adam calls out to her, she returns to her image. It is not until God tells her to go to Adam that she consents to being led from the pool. Like Satan, she is falling prey to the sin of Pride.

Eve first comes into contact with satanic influence in her dreams. After this incident she starts to develop the independent streak that perplexes Adam, particularly when she insists on going off by herself to work in the garden, even though Adam warns her against it.

Once she is alone, Satan tempts her to eat from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. He approaches her in the body of a snake and manipulates her by appealing to her pride and vanity.

Likewise, she soon gets Adam to eat from the tree as well, though he does this because he doesn't want to lose Eve. This creates a complexity that is not in the Biblical version of the story. In this version, Adam reasons that Eve will probably die soon from eating the fruit, so he eats the fruit because he would rather die with her than live alone.

Later, when they don't die and Adam realizes that their actions in the garden have cursed all of mankind, he is harsh on Eve, blaming her for their transgression. At this point, Eve gets on her knees and begs Adam for forgiveness. And since Adam still loves Eve, he forgives her, sharing some of the blame with her.

The Son of God: The Son of God in Paradise Lost is Jesus Christ, though he is never named explicitly, since he has not yet entered human form. The Son is very heroic and powerful, singlehandedly defeating Satan and his followers when they violently rebel against God and driving them into Hell. Also, after the Father explains to him how Adam and Eve shall fall, and how the rest of humanity will be doomed to follow them in their cursed footsteps, the Son selflessly and heroically proclaims that he will take the punishment for humanity. The Son endows hope to the poem, because although Satan conquers humanity by successfully tempting Adam and Eve, the victory is temporary because the Son will save the human race.[8]

God the Father: God the Father is the creator of Eden, Heaven, Hell, and of each of the main characters. While depicted as pompous, irascible, selfish and obnoxious, he is an all-powerful and all-knowing being who cannot be overthrown by even the one-third of the angels Satan incites against him. The poem portrays God’s process of creation in the way that Milton believed it was done, that God created Heaven, Earth, Hell, and all the creatures that inhabit these separate planes from part of Himself, not out of nothing.[9] Thus, according to Milton, the ultimate authority of God derives from his being the "author" of creation. Satan tries to justify his rebellion by denying this aspect of God and claiming self-creation, but he admits to himself this is not the case, and that God "deserved no such return/ From me, whom He created what I was."[10][11]

Raphael: Raphael is an angel who is sent by God to warn Adam about Satan's infiltration of Eden and to warn him that Satan is going to try to curse Adam and Eve. Raphael initially meets with both Adam and Eve but has a private discussion about Satan with Adam only. During this discussion, Raphael tells Adam the story of Satan's rebellion and subsequent exile into Hell. After this, because of Adam's curiosity, Raphael also explains to Adam how God created the Earth and the universe.

Michael: After Adam and Eve disobey God by eating from the Tree of Knowledge, God sends the angel Michael to visit Adam and Eve. His duty is to escort Adam and Eve out of Paradise. But before this happens, Michael shows Adam visions of the future which cover an outline of the Bible, from the story of Cain and Abel in Genesis, up through the story of Jesus in the New Testament. This vision is meant to show Adam what happens to mankind and to show Adam how Jesus will redeem humanity and eventually drive out Satan, Sin, and Death from the Earth.

Abdiel: Of the host of angels that Satan rallies to revolt, Abdiel alone denounces Satan. He then abandons Lucifer to bring the news of his defection to God. However, when he arrives, he finds that preparations are already underway for battle.

[edit] Composition

Milton composed the entire work while completely blind. It is presumed he had glaucoma, necessitating the use of paid amanuenses and his daughters. The poet claimed that a divine spirit inspired him during the night, leaving him with verses that he would recite in the morning.[dubious ]

[edit] Themes

[edit] Marriage

Milton first presents Adam and Eve in Book IV with impartiality. The relationship between Adam and Eve is one of "mutual dependence, not a relation of domination or hierarchy." While the author does place Adam above Eve in regard to his intellectual knowledge, and in turn his relation to God, he also grants Eve the benefit of knowledge through experience. Hermine Van Nuis clarifies that although there is a sense of stringency associated with the specified roles of the male and the female, each unreservedly accepts the designated role because it is viewed as an asset.[12] Instead of believing that these roles are forced upon them, each uses the obligatory requirement as a strength in their relationship with each other. These minor discrepancies reveal the author’s view on the importance of mutuality between a husband and a wife.When examining the relationship between Adam and Eve, critics tend to accept an either Adam-or Eve—centered view in terms of hierarchy and importance to God. David Mikics argues, by contrast, these positions "overstate the independence of the characters' stances, and therefore miss the way in which Adam and Eve are entwined with each other".[13] Milton's true vision reflects one where the husband and wife (in this instance, Adam and Eve) depend on each other and only through each other’s differences are able to thrive.[13] While most readers believe that Adam and Eve fail because of their fall from paradise, Milton would argue that the resulting strengthening of their love for one another is true victory.

Although Milton does not directly mention divorce, critics posit theories on Milton's view of divorce based on inferences found within the poem. Other works by Milton suggest he viewed marriage as an entity separate from the church. Discussing Paradise Lost, Biberman entertains the idea that "marriage is a contract made by both the man and the woman".[14] Based on this inference, Milton would believe that both man and woman would have equal access to divorce, as they do to marriage.

Feminist critics of Paradise Lost suggest that Eve is forbidden the knowledge of her own identity. Moments after her creation, before Eve is led to Adam, she becomes enraptured by an image reflected in the water (her own, unbeknownst to Eve).[15] God urges Eve to look away from her own image, her beauty, which is also the object of Adam’s desire. Adam delights in both her beauty and submissive charms, yet Eve may never be permitted to gaze upon her individual form. Critic Julia M. Walker argues that because Eve “neither recognizes nor names herself ... she can know herself only in relation to Adam.”[16] “Eve’s sense of self becomes important in its absence ... [she] is never allowed to know what she is supposed to see.”[17] Eve therefore knows not what she is, only what she is not: male. Starting in Book IV, Eve learns that Adam, the male form, is superior and “How beauty is excelled by manly grace/ And wisdom which alone is truly fair.”[18] Led by his gentle hand, she yields, a woman without individual purpose, destined to fall by “free will.”

[edit] Idolatry

Milton's 17th century contemporaries by and large criticized Milton’s ideas and considered him as a radical, mostly because of his well-known Protestant views on politics and religion. One of Milton's greatest and most controversial arguments centers on his concept of what is idolatrous; this topic is deeply embedded in Paradise Lost.Milton's first criticism of idolatry focuses on the practice of constructing temples and other buildings to serve as places of worship. In Book XI of Paradise Lost, Adam tries to atone for his sins by offering to build altars to worship God. In response, the angel Michael explains Adam does not need to build physical objects to experience the presence of God.[19] Joseph Lyle points to this example, explaining "When Milton objects to architecture, it is not a quality inherent in buildings themselves he finds offensive, but rather their tendency to act as convenient loci to which idolatry, over time, will inevitably adhere."[20] Even if the idea is pure in nature, Milton still believes that it will unavoidably lead to idolatry simply because of the nature of humans. Instead of placing their thoughts and beliefs into God, as they should, humans tend to turn to erected objects and falsely invest their faith. While Adam attempts to build an altar to God, critics note Eve is similarly guilty of idolatry, but in a different manner. Harding believes Eve's narcissism and obsession with herself constitutes idolatry.[21] Specifically, Harding claims that "... under the serpent’s influence, Eve’s idolatry and self-deification foreshadow the errors into which her 'Sons' will stray."[21] Much like Adam, Eve falsely places her faith into herself, the Tree of Knowledge, and to some extent, the Serpent, all of which do not compare to the ideal nature of God.

Furthermore, Milton makes his views on idolatry more explicit with the creation of Pandemonium and the exemplary allusion to Solomon’s temple. In the beginning of Paradise Lost, as well as throughout the poem, there are several references to the rise and eventual fall of Solomon's temple. Critics elucidate that "Solomon’s temple provides an explicit demonstration of how an artifact moves from its genesis in devotional practice to an idolatrous end."[22] This example, out of the many presented, conveys Milton’s views on the dangers of idolatry distinctly. Even if one builds a structure in the name of God, even the best of intentions can become immoral. In addition, critics have drawn parallels between both Pandemonium and Saint Peter's Basilica,[citation needed] and the Pantheon. The majority of these similarities revolve around a structural likeness, but as Lyle explains, they play a greater role. By linking Saint Peter’s Basilica and the Pantheon to Pandemonium—an ideally false structure, the two famous buildings take on a false meaning.[23] This comparison best represents Milton's Protestant views, as it rejects both the purely Catholic perspective and the Pagan perspective.

In addition to rejecting Catholicism, Milton revolted against the idea of a monarch ruling by divine right. He saw the practice as idolatrous. Barbara Lewalski concludes that the theme of idolatry in Paradise Lost "is an exaggerated version of the idolatry Milton had long associated with the Stuart ideology of divine kingship".[24] In the opinion of Milton, any object, human or non-human, that receives special attention befitting of God, is considered idolatrous.

[edit] Response and criticism

Greece, Italy, and England did adorn.

The First in loftiness of thought surpass'd;

The Next in Majesty; in both the Last.

The force of Nature cou'd no farther goe:

To make a third she joynd the former two."

- The reason Milton wrote in fetters when he wrote of Angels & God, and at liberty when of Devils & Hell, is because he was a true Poet and of the Devil's party without knowing it.

The latter half of the twentieth century saw critical understanding of Milton's epic shift to a more political and philosophical focus. Rather than the Romantic conception of the Devil as hero, it is generally accepted that Satan is presented in terms that begin classically heroic, then diminish him until he is finally reduced to a dust-eating serpent unable even to control his own body. The political angle enters into consideration in the underlying friction between Satan's conservative, hierarchical view of the universe, and the contrasting "new way" of God and the Son of God as illustrated in Book III.[citation needed] In other words, in contemporary criticism the main thrust of the work becomes not the perfidy or heroism of Satan, but rather the tension between classical conservative "Old Testament" hierarchs (evidenced in Satan's worldview and even in that of the archangels Raphael and Gabriel), and "New Testament" revolutionaries (embodied in the Son of God, Adam, and Eve) who represent a new system of universal organization.[citation needed] This new order is based not in tradition, precedence, and unthinking habit, but on sincere and conscious acceptance of faith and on station chosen by ability and responsibility.[citation needed] Naturally, this interpretation makes much use of Milton's other works and his biography, grounding itself in his personal history as an English revolutionary and social critic.[citation needed]

Samuel Johnson praised the poem lavishly, but conceded that "None ever wished it longer than it is."[25]

In Paul Stevens of University of Toronto's Milton's Satan, he claimed the Satan figure was one of the earliest examples of an anti-hero who does not submit to authority, but the actions are greatly based on his own arrogance and delusion. Stevens also claimed Paradise Lost was a story about Milton himself, who wrote in support of events that eventually led to English Civil War.[26] That analysis was debuted in 2009 season of TVO's Best Lecturer series.[27]

[edit] Iconography and cultural references

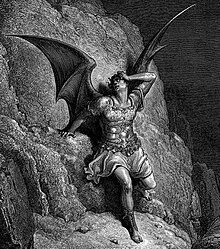

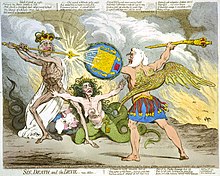

Some of the most notable illustrators of Paradise Lost included William Blake, Gustave Doré and Henry Fuseli (1799); however, the epic's illustrators also include, among others, John Martin, Edward Burney, Richard Westall, Francis Hayman.

Outside of book illustrations, the epic has also inspired other visual works by well-known painters like Salvador Dalí who executed a set of ten colour engravings in 1974.

Milton's achievement in writing Paradise Lost without his sight inspired a more biographical work in a painting by Eugène Delacroix entitled "Milton Dictating Paradise Lost to his Daughters".[29]

Paradise Lost has also inspired works in the fields of music and literature (though not to the degree that the poem has inspired visual artists). One of the most familiar contemporary examples in literature is that of the young-adult fiction trilogy His Dark Materials by Philip Pullman which takes its title from Paradise Lost. Pullman has stated that Milton's poem also directly inspired the basic plot and the central conflict of His Dark Materials.[30]

Musical tributes to the book include an opera version by the Polish composer Krzysztof Penderecki and Joseph Haydn's oratorio The Creation.

[edit] See also

- John Milton's poetic style

- Paradise Regained, a shorter, later poem by Milton about the Temptation of Christ by Satan