Operation Sea Lion

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

Contents[show] |

[edit] Background

By early November 1939, Adolf Hitler had decided on forcing a decision in the West by invading Belgium, Holland and France. With the prospect of the Channel ports falling under Kriegsmarine (German Navy) control and attempting to anticipate the obvious next step that might entail, Grand Admiral (Großadmiral) Erich Raeder (head of the Kriegsmarine) instructed his Operations officer, Kapitän Hans Jürgen Reinicke, to draw up a document examining "the possibility of troop landings in England should the future progress of the war make the problem arise." Reinicke spent five days on this study and set forth the following prerequisites:[3]- Elimination or sealing off of Royal Navy forces from the landing and approach areas.

- Elimination of the Royal Air Force (RAF).

- Destruction of all Royal Navy units in the coastal zone.

- Prevention of British submarine action against the landing fleet.

On 16 July 1940, following Germany's swift and successful occupation of France and the Low Countries and growing impatient with Britain's indifference towards his recent peace overtures, Hitler issued Directive No. 16, setting in motion preparations for a landing in Britain. He prefaced the order by stating: "As England, in spite of her hopeless military situation, still shows no signs of willingness to come to terms, I have decided to prepare, and if necessary to carry out, a landing operation against her. The aim of this operation is to eliminate the English Motherland as a base from which the war against Germany can be continued, and, if necessary, to occupy the country completely."[5]

Hitler's directive set four pre-conditions for the invasion to occur:[6]

- The RAF was to be "beaten down in its morale and in fact, that it can no longer display any appreciable aggressive force in opposition to the German crossing".

- The English Channel was to be swept of British mines at the crossing points, and the Straits of Dover must be blocked at both ends by German mines.

- The coastal zone between occupied France and England must be dominated by heavy artillery.

- The Royal Navy must be sufficiently engaged in the North Sea and the Mediterranean so that it could not intervene in the crossing. British home squadrons must be damaged or destroyed by air and torpedo attacks.

Upon hearing of Hitler's intentions, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini, through his Foreign Minister Count Ciano, quickly offered up to ten divisions and thirty squadrons of Italian aircraft for the proposed invasion.[9] Hitler initially declined any such aid but eventually allowed a small contingent of Italian fighters and bombers, the Italian Air Corps (Corpo Aereo Italiano or CAI), to assist in the Luftwaffe's aerial campaign over Britain in October/November 1940.[10]

[edit] German land forces

[edit] Operation Eagle

Beginning in August 1940, the German Luftwaffe began a series of concentrated aerial attacks (designated Unternehmen Adlerangriff or Operation Eagle Attack) on targets throughout the British Isles in an attempt to destroy the RAF (Royal Air Force) and establish air superiority over Great Britain. The campaign later became known as the Battle of Britain. However, the change in emphasis of the bombing from RAF bases to bombing London turned Adler into a strategic bombing operation. This switch afforded the RAF, reeling from Luftwaffe attacks on its bases, time to pull back and regroup.[edit]

The most daunting problem for Germany in protecting an invasion fleet was the small size of its navy. The Kriegsmarine, already numerically far inferior to Britain's Royal Navy, had lost a sizable portion of its large modern surface units in April 1940 during the Norwegian Campaign, either as complete losses or due to battle damage. In particular, the loss of two light cruisers and ten destroyers was crippling, as these were the very warships most suited to operating in the Channel Narrows where the invasion would likely take place.[11] The U-boats, the most powerful arm of the Kriegsmarine, were simply not suitable for operations in the relatively shallow and restricted waters of the English Channel.Although the Royal Navy could not bring to bear the whole of its naval superiority (most of the fleet was engaged in the Atlantic and Mediterranean), the British Home Fleet still had a very large advantage in numbers. British ships were still vulnerable to enemy air attack, as demonstrated during the Dunkirk evacuation and by the later Japanese sinking of Prince of Wales and Repulse. However, the 22 miles (35 km) width of the English Channel (at its narrowest point — the average width is much greater and no traverse of the Channel would be that short) and the overall disparity between the opposing naval forces made the amphibious invasion plan risky, regardless of the outcome in the air. In addition, the Kriegsmarine had allocated its few remaining larger and modern ships to diversionary operations in the North Sea.

The French fleet, one of the most powerful and modern in the world, might have tipped the balance against Britain. However, the preemptive destruction of the French fleet by the British by an attack on Mers-el-Kébir and the scuttling of the French fleet in Toulon two years later ensured that this could not happen.

Even if the Royal Navy had been neutralised, the chances of a successful amphibious invasion across the channel were remote. The Germans had no specialised landing craft, and had to rely primarily on river barges. This would have limited the quantity of artillery and tanks that could be transported and restricted operations to times of good weather. The barges were not designed for use in open sea and even in almost perfect conditions, they would have been slow and vulnerable to attack. There were also not enough barges to transport the first invasion wave nor the following waves with their equipment. The Germans would have needed to immediately capture a port, an unlikely circumstance considering the strength of the British coastal defences around the south-eastern harbours at that time. The British also had several contingency plans, including the use of poison gas.

[edit] Landing craft

One of the more glaring deficiencies in the German Navy for mounting large-scale amphibious assaults was an almost complete lack of purpose-built landing craft. The Navy had already taken some small steps in remedying this situation with construction of the Pionierlandungsboot 39 (Engineer Landing Boat 39), a self-propelled shallow-draft vessel which could carry 45 infantrymen, two light vehicles or 20 tons of cargo and land on an open beach (unloading via a pair of clamshell doors at the bow). But by late September 1940, only two prototypes had been delivered.[12] Recognizing the need for an even larger craft capable of landing both tanks and infantry onto a hostile shore, the Navy began development of the 220-ton Marinefährprahm (MFP) but these too were unavailable in time for a landing on English soil in 1940, the first of them not being commissioned until April 1941.The obvious solution for the Navy to assemble a large sea-going invasion fleet in the short time allotted was to convert inland river barges to the task. Towards that end, the Kriegsmarine collected approximately 2,400 barges from throughout Europe (860 from Germany, 1,200 from the Netherlands and Belgium and 350 from France). Of these, only about 800 were powered (some insufficiently). The rest required towing by tugs.[13]

[edit] Specialized landing equipment

As part of a Navy competition, prototypes for a prefabricated "heavy landing bridge" or jetty (similar in function to later Allied Mulberry Harbours) were designed and built by Krupp Stahlbau and Dortmunder Union and successfully overwintered in the North Sea in 1941/42.[14] Krupp's design won out, as it only required one day to install as opposed to twenty-eight days for the Dortmunder Union bridge. The Krupp bridge consisted of a series of 32m-long connecting platforms, each supported on the seabed by four steel columns. The platforms could be raised or lowered by heavy-duty winches in order to accommodate the tide. The German Navy initially ordered eight complete Krupp units composed of six platforms each. This was reduced to six units by the Autumn of 1941, and eventually cancelled altogether when it became apparent Sea Lion would never take place.[15]In mid-1942, both the Krupp and Dortmunder prototypes were shipped to the Channel Islands and installed together off Alderney, where they were used for unloading materials needed to fortify the island. Referred to as the "German jetty" by local inhabitants, it remained standing for the next thirty-six years until demolition crews finally removed it in 1978/79, a testament to its durability.[15]

The German Army developed a portable landing bridge of its own nicknamed Seeschlange (Sea Snake). This "floating roadway" was formed from a series of joined modules that could be towed into place to act as a temporary jetty. Moored ships could then unload their cargo either directly onto the roadbed or lower it down onto waiting vehicles via their heavy-duty booms. The Seeschlange was successfully tested by the Army Training Unit at Le Havre in the fall of 1941 and later slated for use in Operation Herkules, the proposed Italo-German invasion of Malta. It was easily transportable by rail.[15]

Specialized vehicles slated for Sea Lion included the Landwasserschlepper (LWS). Under development since 1935, this amphibious tractor was originally intended for use by Army engineers to assist with river crossings. Three of them were assigned to Tank Detachment 100 as part of the invasion and it was intended to use them for pulling ashore unpowered assault barges and towing vehicles across the beaches. They would also have been used to carry supplies directly ashore during the six hours of falling tide when the barges were grounded. This involved towing a Kässbohrer amphibious trailer (capable of transporting 10-20 tons of freight) behind the LWS.[16] The LWS was demonstrated to General Franz Halder on 2 August 1940 by the Reinhardt Trials Staff on the island of Sylt and, though he was critical of its high silhouette on land, he recognized the overall usefulness of the design. It was proposed to build enough tractors that each invasion barge could be assigned one or two of them but the late date and difficulties in mass-producing the vehicle prevented implementation of that plan.[16]

[edit] Broad vs. narrow front

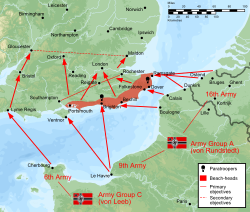

The German Army High Command (Oberkommando des Heeres, or OKH) originally planned an invasion on a vast scale, extending from Dorset to Kent. This was far in excess of what their navy could supply, and final plans were more modest, calling for nine divisions to make an amphibious landing with around 67,000 men in the first echelon and an airborne division to support them.[17] The chosen invasion sites ran from Rottingdean in the west to Hythe in the east.The battle plan called for German forces to be launched from Cherbourg to Lyme Regis, Le Havre to Ventnor and Brighton, Boulogne to Eastbourne, Calais to Folkestone, and Dunkirk and Ostend to Ramsgate. German paratroopers would land near Brighton and Dover. Once the coast was secured, they would push north, taking Gloucester and encircling London.[18] There is reason to believe that the Germans would not attempt to assault the city but besiege and bombard it.[19] German forces would secure England up to the 52nd parallel (approximately as far north as Northampton), anticipating that the rest of the United Kingdom would then surrender.

[edit] German coastal guns

With Germany's occupation of the Pas-de-Calais region in northern France, the possibility of closing the Strait of Dover to Royal Navy warships and merchant convoys by use of land-based heavy artillery became readily apparent, both to the German High Command and to Hitler. Even the Kriegsmarine’s Naval Operations Office deemed this a plausible and desirable goal, especially given the relatively short distance, 34 km (21 mi), between the French and English coasts. Orders were therefore issued to assemble and begin emplacing every Army and Navy heavy artillery piece available along the French coast, primarily at Pas-de-Calais. This work was assigned to Organisation Todt and commenced on 22 July 1940.[20]By early August, four 28 cm (11 in) traversing turrets were fully operational as were all of the Army’s railway guns. Seven of the railway guns, six 28 cm K5 guns and a single 21 cm (8.3 in) K12 gun with a range of 115 km (71 mi), could only be used against land targets. The remainder, thirteen 28 cm guns and five 24 cm (9.4 in) guns, plus additional motorized batteries comprising twelve 24 cm guns and ten 21 cm guns, could be fired at shipping but were of limited effectiveness due to their slow traverse speed, long loading time and ammunition types.[21]

Better suited for use against naval targets were the four heavy naval batteries installed by mid-September: Friedrich August with three 30.5 cm (12.0 in) guns; Prinz Heinrich with two 28 cm guns; Oldenburg with two 24 cm guns and, largest of all, Siegfried (later renamed Batterie Todt) with a pair of 38 cm (15 in) guns. Fire control for these guns was provided by both spotter aircraft and by DeTeGerät radar sets installed at Blanc Nez and Cap d’Alprech. These units were capable of detecting targets out to a range of 40 km (25 mi), including small British patrol craft inshore of the English coast. Two additional radar sites were added by mid-September: a DeTeGerät at Cap de la Hague and a FernDeTeGerät long-range radar at Cap d’Antifer near Le Havre.[22]

To strengthen German control of the Channel Narrows, the Army planned to quickly establish mobile artillery batteries along the English shoreline once a beachhead had been firmly established. Towards that end, 16th Army’s Artillerie Kommand 106 was slated to land with the second wave to provide fire protection for the transport fleet as early as possible. This unit consisted of 24 15 cm (5.9 in) guns and 72 10 cm (3.9 in) guns. About one third of them were to be deployed on English soil by the end of Sea Lion’s first week.[23]

The presence of these batteries was expected to greatly reduce the threat posed by British destroyers and smaller craft along the eastern approaches as the guns would be sited to cover the main transport routes from Dover to Calais and Hastings to Boulogne. They could not entirely protect the western approaches, but a large area of those invasion zones would still be within effective range.[23]

The British military was well aware of the dangers posed by German artillery dominating the Dover Strait and on 4 September 1940 the Chief of Naval Staff issued a memo stating that if the Germans "...could get possession of the Dover defile and capture its gun defences from us, then, holding these points on both sides of the Straits, they would be in a position largely to deny those waters to our naval forces". Should the Dover defile be lost, he concluded, the Royal Navy could do little to interrupt the flow of German supplies and reinforcements across the Channel, at least by day, and he further warned that "...there might really be a chance that they (the Germans) might be able to bring a serious weight of attack to bear on this country". The very next day the Chiefs of Staff, after discussing the importance of the defile, decided to reinforce the Dover coast with more ground troops.[24]

[edit] Cancellation

On 17 September 1940, Hitler held a meeting with Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring and Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt. Hitler became convinced that the operation was not viable. Control of the skies was lacking, and coordination among three branches of the armed forces was out of the question. Later that day, Hitler ordered the postponement of the operation.The postponement coincided with a rumour that there had been an attempt to land on British shores at Shingle Street, but it had been repulsed with large German casualties. This was reported in the American press, and in William L. Shirer's Berlin Diary but was officially denied. British papers, declassified in 1993, have suggested this was a successful example of British black propaganda to bolster morale in Britain, America and occupied Europe.[25]

After the London Blitz, Hitler turned his attention to the Soviet Union, and Seelöwe lapsed, never to be resumed. However, not until 13 February 1942, after the invasion of Russia, were forces earmarked for the operation released to other duties.[26]