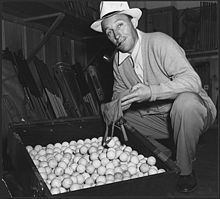

Bing Crosby

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page.

|

| Bing Crosby | |

|---|---|

Crosby in Road to Singapore (1940) | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Harry Lillis Crosby |

| Born | May 3, 1903[1] Tacoma, Washington, U.S. |

| Origin | Spokane, Washington, U.S. |

| Died | October 14, 1977 (aged 74) Madrid, Spain |

| Genres | Traditional pop, Jazz, vocal[2] |

| Occupations | Singer, actor |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Years active | 1926–77 |

| Labels | Brunswick, Decca, Reprise, RCA Victor, Verve, United Artists |

| Associated acts | Bob Hope, Dixie Lee, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Fred Astaire, The Rhythm Boys, Rosemary Clooney, David Bowie, Louis Armstrong |

| Website | http://www.bingcrosby.com |

One of the first multimedia stars, from 1934 to 1954 Bing Crosby was very successful across record sales, radio ratings and motion picture grosses.[5] Crosby and his musical acts influenced male singers of the era that followed him, including Perry Como,[6] Frank Sinatra, and Dean Martin. Yank magazine recognized Crosby as the person who had done the most for American G.I. morale during World War II and, during his peak years, around 1948, polls declared him the "most admired man alive," ahead of Jackie Robinson and Pope Pius XII.[7][8] Also during 1948, the Music Digest estimated that Crosby recordings filled more than half of the 80,000 weekly hours allocated to recorded radio music.[8]

Crosby exerted an important influence on the development of the postwar recording industry. In 1947, he invested $50,000 in the Ampex company, which developed North America's first commercial reel-to-reel tape recorder, and Crosby became the first performer to pre-record his radio shows and master his commercial recordings on magnetic tape. He gave one of the first Ampex Model 200 recorders to his friend, musician Les Paul, which led directly to Paul's invention of multitrack recording. Along with Frank Sinatra, he was one of the principal backers behind the famous United Western Recorders studio complex in Los Angeles.[9]

Through the aegis of recording, Crosby developed the techniques of constructing his broadcast radio programs with the same directorial tools and craftsmanship (editing, retaking, rehearsal, time shifting) that occurred in a theatrical motion picture production. This feat directly led the way to applying the same techniques to creating all radio broadcast programming as well as later television programming. The quality of the recorded programs gave them commercial value for re-broadcast. This led the way to the syndicated market for all short feature media such as TV series episodes.[citation needed]

In 1962, Crosby was the first person to be recognized with the Grammy Global Achievement Award.[10] He won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as Father Chuck O'Malley in the 1944 motion picture Going My Way, and was nominated for his reprisal of Father O'Malley in The Bells of St. Mary's the very next year, the only actor to be nominated twice for the same character performance. Crosby is one of the few people to have three stars on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Contents[show] |

[edit] Early life

Crosby was born in Tacoma, Washington, on May 3, 1903,[1] in a house his father built at 1112 North J Street.[11] In 1906, Crosby's family moved to Spokane, Washington.[12] In 1913, Crosby's father built a house at 508 E. Sharp Ave.[13] The house now sits on the campus of Bing's alma mater Gonzaga University and formerly housed the Alumni Association.He was the fourth of seven children: five boys, Larry (1895–1975), Everett (1896–1966), Ted (1900–1973), Harry 'Bing' (1903–1977), and Bob (1913–1993); and two girls, Catherine (1904–1974) and Mary Rose (1906–1990). His parents, Harry Lincoln Crosby (1870–1950), a bookkeeper, and Catherine Helen (known as Kate) Harrigan (1873–1964), were English-American and Irish-American, respectively. Kate was the daughter of Canadian-born parents who had emigrated to Stillwater, Minnesota, from Miramichi, New Brunswick. Kate's grandfather and grandmother, Dennis and Catherine Harrigan, had in turn moved to Canada in 1831 from Schull, County Cork, Ireland.[14] Bing's paternal ancestors include Governor Thomas Prence and Patience Brewster, who were both born in England and who emigrated to what would become the U.S. in the 17th century. Patience was a daughter of Elder William Brewster (pilgrim), (c. 1567 – April 10, 1644), the Pilgrim leader and spiritual elder of the Plymouth Colony and a passenger on the Mayflower.[15]

In 1910, Crosby was forever renamed. Six-year-old Harry discovered a full-page feature in the Sunday edition of the Spokesman-Review, "The Bingville Bugle".[16][17]

As documented by biographer Gary Giddins in Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams - The Early Years, 1903 - 1940, Volume I, the "Bugle," written by humorist Newton Newkirk, was a parody of a hillbilly newsletter complete with gossipy tidbits, minstrel quips, creative spelling, and mock ads. A neighbor, 15-year-old Valentine Hobart, shared Crosby's enthusiasm for "The Bugle" and noting Crosby's laugh, took a liking to him and called him "Bingo from Bingville". The last vowel was dropped and the name shortened to "Bing", which stuck.[18]

In 1917, Crosby took a summer job as property boy at Spokane's "Auditorium," where he witnessed some of the finest acts of the day, including Al Jolson, who held Crosby spellbound with his ad libbing and spoofs of Hawaiian songs. Crosby later described Jolson's delivery as "electric".[19]

[edit] Popular success

[edit] Music

In 1926, while singing at Los Angeles Metropolitan Theater, Crosby and his vocal duo partner Al Rinker caught the eye of Paul Whiteman, arguably the most famous bandleader at the time. Hired for $150 a week, they made their debut on December 6, 1926 at the Tivoli Theatre (Chicago). Their first recording, "I've Got The Girl," with Don Clark's Orchestra, was issued by Columbia and did them no vocal favors as it sounded as if they were singing in a key much too high for them. It was later revealed that the 78 rpm was recorded at a speed slower than it should have been, which increased the pitch when played at 78 rpm.As popular as the Crosby and Rinker duo was, Whiteman added another member to the group, pianist and aspiring songwriter Harry Barris. Whiteman dubbed them The Rhythm Boys, and they joined the Whiteman vocal team, working and recording with musicians Bix Beiderbecke, Jack Teagarden, Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, and Eddie Lang and Hoagy Carmichael.

Crosby soon became the star attraction of the Rhythm Boys, not to mention Whiteman's band, and in 1928 had his first number one hit, a jazz-influenced rendition of "Ol' Man River". However, his repeated youthful peccadilloes and growing dissatisfaction with Whiteman forced him, along with the Rhythm Boys, to leave the band and join the Gus Arnheim Orchestra. During his time with Arnheim, The Rhythm Boys were increasingly pushed to the background as the vocal emphasis focused on Crosby. Fellow member of The Rhythm Boys Harry Barris wrote several of Crosby's subsequent hits including "At Your Command," "I Surrender Dear", and "Wrap Your Troubles In Dreams"; however, shortly after this, the members of the band had a falling out and split, setting the stage for Crosby's solo career.[20]

On September 2, 1931, Crosby made his solo radio debut.[21] In 1931, he signed with Brunswick Records and recording under Jack Kapp and signed with CBS Radio to do a weekly 15 minute radio broadcast; almost immediately he became a huge hit.[20] His songs "Out of Nowhere", "Just One More Chance", "At Your Command" and "I Found a Million Dollar Baby (in a Five and Ten Cent Store)" were among the best selling songs of 1931.[20]

As the 1930s unfolded, it became clear that Bing was the number one man, vocally speaking. Ten of the top 50 songs for 1931 either featured Crosby solo or with others. Apart from the short-lived "Battle of the Baritones" with Russ Columbo, "Bing Was King," signing long-term deals with Jack Kapp's new record company Decca and starring in his first full-length features, 1932's The Big Broadcast, the first of 55 such films in which he received top billing. He appeared in 79 pictures.

Around this time Crosby co-starred on radio with The Carl Fenton Orchestra on a popular CBS radio show, and by 1936 replacing his former boss, Paul Whiteman, as the host of NBC's Kraft Music Hall, a weekly radio program where he remained for the next ten years. As his signature tune he used "Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)", which also showcased his whistling skill.

He was thus able to take popular singing beyond the kind of "belting" associated with a performer like Al Jolson, who had to reach the back seats in New York theatres without the aid of the microphone. With Crosby, as Henry Pleasants noted in The Great American Popular Singers, something new had entered American music, something that might be called "singing in American," with conversational ease. The oddity of this new sound led to the epithet "crooner".

Crosby gave great emphasis to live appearances before American troops fighting in the European Theater. He also learned how to pronounce German from written scripts and would read propaganda broadcasts intended for the German forces. The nickname "der Bingle" for him was understood to have become current among German listeners, and came to be used by his English-speaking fans. In a poll of U.S. troops at the close of World War II, Crosby topped the list as the person who did the most for G.I. morale, beating President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, General Dwight Eisenhower, and Bob Hope.

Crosby's biggest musical hit was his recording of Irving Berlin's "White Christmas", which he introduced through a 1942 Christmas-season radio broadcast and the movie Holiday Inn. Crosby's recording hit the charts on October 3, 1942, and rose to #1 on October 31, where it stayed for 11 weeks. In the following years, his recording hit the Top 30 pop charts another 16 times, topping the charts again in 1945 and January 1947. The song remains Crosby's best-selling recording, and the best-selling single and best-selling song of all time.[20] In 1998, after a long absence, his 1947 version hit the charts in Britain, and as of 2006[update] remains the North American holiday-season standard. According to Guinness World Records, Crosby's recording of "White Christmas" has "sold over 100 million copies around the world, with at least 50 million sales as singles."[22] His 1948 song Now is the Hour, however, would be his last number one hit.[20]

[edit] Motion pictures

According to ticket sales, Crosby is, at 1,077,900,000 tickets sold, the third most popular actor of all time, behind Clark Gable and John Wayne.[23] Crosby is, according to Quigley Publishing Company's International Motion Picture Almanac, tied for second on the "All Time Number One Stars List" with Clint Eastwood, Tom Hanks, and Burt Reynolds.[24] Crosby's most popular film, White Christmas, grossed $30 million in 1954 ($243 million in current value).[25] Crosby won an Academy Award for Best Actor for Going My Way in 1944, a role he reprised in the 1945 sequel The Bells of Saint Mary's, for which he was nominated for another Academy Award for Best Actor. He received critical acclaim for his performance as an alcoholic entertainer in The Country Girl, receiving his third Academy Award nomination. He partnered with Bob Hope in seven Road to musical comedies between 1940 and 1962 and the two actors remained linked for generations in general public perception as arguably the most popular screen team in film history, despite never officially declaring themselves a "team" in the sense that Laurel and Hardy or Martin and Lewis were teams.By the late 1950s, Crosby's singing career would make a comeback, with his albums Bing Sings Whilst Bregman Swings and Bing With A Beat selling reasonable well,[20] and the adolescence of the baby boom generation began to affect record sales to younger customers. In 1960, Crosby starred in High Time, a collegiate comedy with Fabian and Tuesday Weld that foretold the emerging gap between older Crosby fans and a new generation of films and music. During the 1960s, Crosby's career in entertainment was in a great decline.[20]

[edit] Television

The Fireside Theater (1950) was Crosby's first television production. The series of 26-minute shows was filmed at Hal Roach Studios rather than performed live on the air. The "telefilms" were syndicated to individual television stations.Crosby was one of the most frequent guests on the musical variety shows of the 1950s and 1960s. He was especially closely associated with ABC's variety show The Hollywood Palace. He was the show's most frequent guest host and appeared annually on its Christmas edition with his wife Kathryn and his younger children. In the early 1970s he made two famous late appearances on the Flip Wilson Show, singing duets with the comedian. Crosby's last TV appearance was a Christmas special filmed in London in September 1977 and aired just weeks after his death.

Bing Crosby Productions, affiliated with Desilu Studios and later CBS Television Studios, produced a number of television series, including Crosby's own unsuccessful ABC sitcom The Bing Crosby Show in the 1964–1965 season (with co-stars Beverly Garland and Frank McHugh), and two ABC medical dramas, Ben Casey (1961–1966) and Breaking Point (1963–64), and the popular Hogan's Heroes military comedy on CBS, as well as the lesser-known show Slattery's People (1964–1965).

[edit] Style

Crosby was the first singer to use the intimacy of the microphone, rather than the deep, loud Vaudeville style, popular by Al Jolson and others. He brought love and appreciation of jazz music to his singing (Mildred Bailey, sister of Al Rinker, had introduced him to Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith prior to his joining Whiteman). Within the framework of the novelty singing style of The Rhythm Boys, Crosby bent notes and added off-tune phrasing that were firmly rooted in jazz.Crosby also elaborated on a further idea of Al Jolson's, one that Frank Sinatra would ultimately extend: phrasing, or the art of making a song's lyric ring true. "I used to tell (Sinatra) over and over," said Tommy Dorsey, "there's only one singer you ought to listen to and his name is Crosby. All that matters to him is the words, and that's the only thing that ought to for you, too."

During the early portion of his solo career (about 1931-1934), Crosby's emotional, often pleading style of crooning was extremely popular, but Jack Kapp (manager of Brunswick and later Decca) successfully talked Crosby into dropping many of those jazzy mannerisms, in favor of a straight-ahead clear vocal style.

The greatest trick of Crosby's virtuosity was covering it up. It is often said[by whom?][citation needed] that Crosby made his singing and acting "look easy," or as if it were no work at all: he simply was the character he portrayed, and his singing, being a direct extension of conversation, came just as naturally to him as talking, or even breathing. Journalist Donald Freeman said of Crosby, "There is only one Bing Crosby and – the time has come now to face the issue squarely – he happens to be that unique, awesome creature, an artist."

[edit] Vocal characteristics

[edit] Career statistics

Crosby's sales and chart statistics place him among the most popular and successful musical acts of the 20th century. Although the Billboard charts operated under a different methodology for the bulk of Crosby's career, his numbers remain astonishing: 1,700 recordings, 383 of those in the top 30, and of those, 41 hit #1. Crosby had separate charting singles in every calendar year between 1931 and 1954; the annual re-release of White Christmas extended that streak to 1957. He had 24 separate popular singles in 1939 alone. Billboard's statistician Joel Whitburn determined Crosby to be America's most successful act of the 1930s, and again in the 1940s.He collected 23 gold and platinum records, according to Joseph Murrells, author of the book, "Million Selling Records." The Recording Industry Association of America did not institute its gold record certification program until 1958, by which point Crosby's record sales were barely a blip, so gold records prior to that year were awarded by an artist's record company. Universal Music, current owner of Crosby's Decca catalog, has never requested RIAA certification for any of his hit singles.

In 1962, Crosby became the first recipient of the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award. He has been inducted into the halls of fame for both radio and popular music. Crosby is a member of the exclusive club of the biggest record sellers that include Elvis Presley, The Beatles, ABBA, Michael Jackson, and Queen.

In 2007 Crosby was inducted into the Hit Parade Hall of Fame, and in 2008 into the Western Music Hall of Fame.[27]

[edit] Entrepreneurship

[edit] Mass media

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding reliable references. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (January 2007) |

Crosby's influence eventually factored into the further development of magnetic tape sound recording and the radio industry's adoption of it.[28][29][30] He used his power to innovate new methods of reproducing audio of himself. But with NBC (and competitor CBS) refusing to allow recorded radio programs (except for advertisements and occasional promotional material), Crosby walked away from the network and stayed off the air for seven months, causing a legal battle with Kraft, his sponsor, that was settled out of court and put Crosby back on the air for the last 13 weeks of the 1945–1946 season.

The Mutual network, on the other hand, had pre-recorded some of its programs as early as the Summer 1938 run of The Shadow with Orson Welles, and the new ABC network – formed out of the sale of the old NBC Blue network in 1943 to Edward Noble, the "Life Savers King," following a federal anti-trust action – was willing to join Mutual in breaking the tradition. ABC offered Crosby $30,000 per week to produce a recorded show every Wednesday sponsored by Philco. He would also get $40,000 from 400 independent stations for the rights to broadcast the 30-minute show that was sent to them every Monday on three 16-inch lacquer/aluminum discs that played ten minutes per side at 33⅓ rpm.

Crosby wanted to change to recorded production for several reasons. The legend that has been most often told is that it would give him more time for his golf game. And he did record his first Philco program in August 1947 so he could enter the Jasper National Park Invitational Golf Tournament in September when the new radio season was to start. But golf was not the most important reason.

Crosby was always an early riser and hard worker, and Dunning and other radio historians have noted that, even while acknowledging he wanted more time to tend his other business and leisure activities. But he also sought better quality through recording, including being able to eliminate mistakes and control the timing of his show performances. Because his own Bing Crosby Enterprises produced the show, he could purchase the latest and best sound equipment and arrange the microphones his way; mic placement had long been a hotly debated issue in every recording studio since the beginning of the electrical era. No longer would he have to wear the hated toupee on his head previously required by CBS and NBC for his live audience shows (he preferred a hat). He could also record short promotions for his latest investment, the world's first frozen orange juice to be sold under the brand name Minute Maid. This investment allowed Bing to make more money by finding a loophole whereby the IRS couldn't tax him at 77% for income, see TIME Magazine story.

The transcription method had problems, however. The acetate surface coating of the aluminum discs was little better than the wax that Edison had used at the turn of the century, with the same limited dynamic range and frequency response.

But Murdo MacKenzie of Bing Crosby Enterprises saw a demonstration of the German Magnetophon in June 1947, one that Jack Mullin had brought back from Radio Frankfurt with 50 reels of tape at the end of the war. This machine was one of the magnetic tape recorders that BASF and AEG had built in Germany starting in 1935. The 6.5mm ferric-oxide-coated tape could record 20 minutes per reel of high-quality sound. Alexander M. Poniatoff ordered his Ampex company (founded in 1944 from his initials A.M.P. plus the starting letters of "excellence") to manufacture an improved version of the Magnetophone.

Crosby hired Mullin and his German machine to start recording his Philco Radio Time show in August 1947, with the same 50 reels of I.G. Farben magnetic tape that Mullin had found at a radio station at Bad Nauheim near Frankfurt while working for the U.S. Army Signal Corps. The crucial advantage was editing. As Crosby wrote in his autobiography, "By using tape, I could do a thirty-five or forty-minute show, then edit it down to the twenty-six or twenty-seven minutes the program ran. In that way, we could take out jokes, gags, or situations that didn't play well and finish with only the prime meat of the show; the solid stuff that played big. We could also take out the songs that didn't sound good. It gave us a chance to first try a recording of the songs in the afternoon without an audience, then another one in front of a studio audience. We'd dub the one that came off best into the final transcription. It gave us a chance to ad lib as much as we wanted, knowing that excess ad libbing could be sliced from the final product. If I made a mistake in singing a song or in the script, I could have some fun with it, then retain any of the fun that sounded amusing."

Mullin's 1976 memoir of these early days of experimental recording agrees with Crosby's account: "In the evening, Crosby did the whole show before an audience. If he muffed a song then, the audience loved it – thought it was very funny – but we would have to take out the show version and put in one of the rehearsal takes. Sometimes, if Crosby was having fun with a song and not really working at it, we had to make it up out of two or three parts. This ad lib way of working is commonplace in the recording studios today, but it was all new to us."

Crosby invested US$50,000 in Ampex to produce more machines. In 1948, the second season of Philco shows was taped with the new Ampex Model 200 tape recorder (introduced in April) using the new Scotch 111 tape from the Minnesota Mining and Manufacturing (3M) company. Mullin explained that new techniques were invented on the Crosby show with these machines: "One time Bob Burns, the hillbilly comic, was on the show, and he threw in a few of his folksy farm stories, which of course were not in Bill Morrow's script. Today they wouldn't seem very off-color, but things were different on radio then. They got enormous laughs, which just went on and on. We couldn't use the jokes, but Bill asked us to save the laughs. A couple of weeks later he had a show that wasn't very funny, and he insisted that we put in the salvaged laughs. Thus the laugh-track was born." Crosby had launched the tape recorder revolution in America. In his 1950 film Mr. Music, Bing Crosby can be seen singing into one of the new Ampex tape recorders that reproduced his voice better than anything else. Also quick to adopt tape recording was his friend Bob Hope, who would make the famous "Road to..." films with Crosby and Dorothy Lamour.

Mullin continued to work for Crosby to develop a videotape recorder. Television production was mostly live in its early years, but Crosby wanted the same ability to record that he had achieved in radio. The Fireside Theater, sponsored by Procter and Gamble, was his first television production for the 1950 season. Mullin had not yet succeeded with videotape, so Crosby filmed the series of 26-minute shows at the Hal Roach Studios. The "telefilms" were syndicated to individual television stations.

Crosby did not remain a television producer but continued to finance the development of videotape. Bing Crosby Enterprises (BCE), gave the world's first demonstration of a videotape recording in Los Angeles on November 11, 1951. Developed by John T. Mullin and Wayne R. Johnson since 1950, the device gave what were described as "blurred and indistinct" images, using a modified Ampex 200 tape recorder and standard quarter-inch (6.3 mm) audio tape moving at 360 inches (9.1 m) per second.[31] Mullin demonstrated an improved picture on December 30, 1952, but he was not able to solve the problem of high tape speed. It was the Ampex team led by Charles Ginsburg that made the first videotape recorder. Rather than speeding tape across fixed heads at 100 ips, Ginsburg used rotating heads to record video tracks transversely at a slant across the tape's width on 2-inch-wide tape moving at only 15 ips. The quadruplex scan model VR-1000 was demonstrated at the National Association of Broadcasters show in Chicago on April 14, 1956, and was an immediate success. Ampex made $4 million in sales during the NAB convention. By this time, Crosby had sold his videotape interests to the 3M company and no longer played the role of tape recorder pioneer. Yet his contribution had been crucial. He had opened the door to Mullin's machine in 1948 and financed the early years of the Ampex company. The rapid spread of the tape recorder revolution was in no small measure caused by Crosby's efforts.

The decade following the end of World War II witnessed what has been called the "revolution in sound." The Decca Company introduced FFRR (Full Frequency Range Recording) 78 rpm records that had the finest frequency response (80–15,000 cps) of any recording process before magnetic tape recording. Decca's method of reducing the size of the groove and designing a delicate elliptical stylus to track on the sides of the groove would be the same innovation of the new microgroove process introduced by Columbia in 1948 on the new 33⅓ rpm LP vinyl record. Crosby's sponsor Philco would join Columbia in selling a new $29.95 record player with jeweled stylus (not steel) tracking at only 10 grams (not 200) for these LPs. No longer would records wear out after 75 plays. Crosby's Ampex Company would be joined by Magnecord, Webcor, Revere, and Fairchild in selling one million tape recorders to a rapidly growing consumer audio component market by 1953. The 1949 Magnecord tape recorder had stereo capability eight years before any vinyl record had it. These components soon began to feature the transistor invented by Bell Labs in 1948.

[edit] Thoroughbred horse racing

Crosby was a fan of Thoroughbred horse racing and bought his first racehorse in 1935. In 1937, he became a founding partner and member of the Board of Directors of the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club that built and operated the Del Mar Racetrack at Del Mar, California. One of Crosby's closest friends was Lindsay Howard, for whom he named his son Lindsay and from whom he would purchase his 40-room Hillsborough estate in 1965. Lindsay Howard was the son of millionaire businessman Charles S. Howard, who owned a successful racing stable that included Seabiscuit. Charles S. Howard joined Crosby as a founding partner and director of the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club.Crosby and Lindsay Howard formed Binglin Stable to race and breed thoroughbred horses at a ranch in Moorpark in Ventura County, California. They also established the Binglin stock farm in Argentina, where they raced horses at Hipódromo de Palermo in Palermo, Buenos Aires. Binglin stable purchased a number of Argentine-bred horses and shipped them back to race in the United States. On August 12, 1938, the Del Mar Thoroughbred Club hosted a $25,000 winner-take-all match race won by Charles S. Howard's Seabiscuit over Binglin Stable's Ligaroti. Binglin's horse Don Bingo won the 1943 Suburban Handicap at Belmont Park in Elmont, New York.

The Binglin Stable partnership came to an end in 1953 as a result of a liquidation of assets by Crosby in order to raise the funds necessary to pay the federal and state inheritance taxes on his deceased wife's estate.[32]

A friend of jockey Johnny Longden, Crosby was a co-owner with Longden's friend Max Bell of the British colt Meadow Court, which won the 1965 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes and the Irish Derby. In the Irish Derby's winner's circle at the Curragh, Crosby sang "When Irish Eyes Are Smiling."

The Bing Crosby Breeders' Cup Handicap at Del Mar Racetrack is named in his honor.

[edit] Personal life

Crosby was married twice, first to actress/nightclub singer Dixie Lee from 1930 until her death from ovarian cancer in 1952. They had four sons: Gary, twins Dennis and Phillip, and Lindsay. The 1947 film Smash-Up: The Story of a Woman is indirectly based on her life. After Dixie's death, Crosby had a relationship with actress Inger Stevens and with Grace Kelly before marrying the actress Kathryn Grant in 1957. They had three children, Harry (who played Bill in Friday the 13th), Mary (best known for portraying Kristin Shepard, the woman who shot J.R. Ewing on TV's Dallas), and Nathaniel.Crosby was a member of the Roman Catholic Church. Kathryn converted to Roman Catholicism in order to marry him. He was also a Republican, and actively campaigned for Wendell Willkie in 1940, asserting his belief that Franklin Roosevelt should serve only two terms. When Willkie lost, he decreed that he would never again make any open political contributions.

Crosby had an interest in sports. From 1946 until the end of his life, he was part-owner of baseball's Pittsburgh Pirates and helped form the nucleus of the Pirates' 1960 championship club. Although he was passionate about his team, he was too nervous to watch the deciding Game 7 of that year's World Series, choosing to go to Paris with Kathryn and listen to the game on the radio. Crosby had the NBC telecast of the game, capped off by Bill Mazeroski's walk-off home run, recorded on kinescope. He apparently viewed the complete film once at his home and then stored it in his wine cellar, where it remained undisturbed until it was discovered in December 2009.[33] In 1978, he and Bob Hope were voted the Bob Jones Award, the highest honor given by the United States Golf Association in recognition of distinguished sportsmanship in golf.

Crosby reportedly overindulged in alcohol in his youth, and may have been dismissed from Paul Whiteman's orchestra because of it, but he later got a handle on his drinking. A 2001 biography of Crosby by Village Voice jazz critic Gary Giddins says that Louis Armstrong's influence on Crosby "extended to his love of marijuana." Bing smoked it during his early career when it was legal and "surprised interviewers" in the 1960s and 70s by advocating its decriminalization, as did Armstrong. According to Giddins, Crosby told his son Gary to stay away from alcohol ("It killed your mother"[34]) and suggested he smoke pot instead.[34] Gary said, "There were other times when marijuana was mentioned and he'd get a smile on his face."[34] Gary thought his father's pot smoking had influenced his easy-going style in his films. He finally quit smoking his pipe following lung surgery in 1974.

At the conclusion of his work in England, Crosby flew alone to Spain to hunt and play golf. Shortly after 6 p.m. on October 14, Crosby died suddenly from a massive heart attack after a round of 18 holes of golf near Madrid where he and his Spanish golfing partner had just defeated their opponents. It is widely written that his last words were "That was a great game of golf, fellas."[35] In Bob Hope's 1985 book Bob Hope's Confessions of A Hooker. My Lifelong Love affair With Golf, Hope recounts hearing Crosby had been advised by a physician in England to only play 9 holes of golf due to his heart condition.

After Crosby's death, his eldest son, Gary, wrote a highly critical memoir, Going My Own Way, depicting his father as cold, remote, and both physically and psychologically abusive.

Younger son Phillip frequently disputed his brother Gary's claims about their father. In an interview conducted in 1999 by the Globe, Phillip said:

However, Crosby's other sons, Lindsay and Dennis, sided with Gary's claim and stated Crosby abused them as well.[37] Dennis also stated that Crosby would abuse Gary the most often.[37]My dad was not the monster my lying brother said he was; he was strict, but my father never beat us black and blue, and my brother Gary was a vicious, no-good liar for saying so. I have nothing but fond memories of Dad, going to studios with him, family vacations at our cabin in Idaho, boating and fishing with him. To my dying day, I'll hate Gary for dragging Dad's name through the mud. He wrote Going My Own Way out of greed. He wanted to make money and knew that humiliating our father and blackening his name was the only way he could do it. He knew it would generate a lot of publicity. That was the only way he could get his ugly, no-talent face on television and in the newspapers. My dad was my hero. I loved him very much. He loved all of us too, including Gary. He was a great father.[36]

Phillip Crosby died in 2004.[38]

Denise Crosby, Dennis's daughter, is also an actress and known for her role as Tasha Yar on Star Trek: The Next Generation, and for the recurring role of the Romulan Sela (daughter of Tasha Yar) after her withdrawal from the series as a regular cast member. She also appeared in the film adaptation of Stephen King's novel Pet Sematary.

Nathaniel Crosby, Crosby's youngest son from his second marriage, was a high-level golfer who won the U.S. Amateur at age 19 in 1981, the youngest winner of that event (a record later broken by Tiger Woods). Nathaniel praised his father in a June 16, 2008, Sports Illustrated article.[39]

Widow Kathryn Crosby dabbled in local theater productions intermittently, and appeared in television tributes to her late husband.

In 2006, Crosby's niece, Carolyn Schneider, published "Me and Uncle Bing," in which she offered an intimate glimpse of her family, and gratitude for Crosby's generosity to her and to other family members.

[edit] Legacy

The family has established an official website.[41] It was launched October 14, 2007, the 30th anniversary of Bing's death.

In his 1990 autobiography Don't Shoot, It's Only Me! Bob Hope states, "Dear old Bing. As we called him, the Economy-sized Sinatra. And what a voice. God I miss that voice. I can't even turn on the radio around Christmastime without crying anymore."[42]

Calypso musician Roaring Lion wrote a tribute song in 1939 entitled "Bing Crosby", in which he wrote: "Bing has a way of singing with his very heart and soul / Which captivates the world / His millions of listeners never fail to rejoice / At his golden voice..."[43]

[edit] Golf

Crosby is a member of the World Golf Hall of Fame. Aside from Bobby Jones and Arnold Palmer, Crosby may be the person most responsible for popularizing the game of golf. Since 1937 the 'Crosby Clambake' as it was popularly known—now the AT&T Pebble Beach National Pro-Am—has been a leading event in the world of professional golf. Crosby first took up the game at 12 as a caddy, dropped it, and started again in 1930 with some fellow cast members in Hollywood during the filming of The King of Jazz. Although he made his name as a singer, vaudeville performer, and silver screen luminary, he would probably prefer to be remembered as a two handicap who competed in both the British and U.S. Amateur championships, a five-time club champion at Lakeside Golf Club in Hollywood, and as one of only a few players to have made a hole-in-one on the 16th at Cypress Point.He conceived his tournament as a friendly little pro-am for his fellow members at Lakeside Golf Club and any stray touring pros who could use some pocket change. The first Clambake was played at Rancho Santa Fe C.C., in northern San Diego county, where Crosby was a member. He kicked in $3,000 of his own money for the purse, which led inaugural champion Sam Snead to ask if he might get his $700 in cash instead of a check. Snead's suspicions notwithstanding, the tournament was a rollicking success, thanks to the merry membership of Lakeside, an entertainment industry enclave in North Hollywood. That first tournament set the precedent for all that followed as it was as much about partying as it was about golf.[44]

The tournament, revived on the Monterey Peninsula in 1947, has as of 2009 raised $93 million for local charities.[45]

[edit] Compositions

Crosby co-wrote lyrics to 15 songs. His composition "At Your Command" was no.1 for three weeks on the U.S. pop singles chart in 1931, beginning with the week of August 8, 1931. "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You" was his most successful composition, recorded by Duke Ellington, Linda Ronstadt, Thelonious Monk, Billie Holiday, and Mildred Bailey. The songs Crosby co-wrote are:- "That's Grandma" (1927), with Harry Barris and James Cavanaugh

- "From Monday On" (1928), with Harry Barris and recorded with the Paul Whiteman Orchestra featuring Bix Beiderbecke on cornet, no. 14 on US pop singles charts

- "What Price Lyrics?" (1928), with Harry Barris and Matty Malneck

- "At Your Command" (1931), with Harry Barris and Harry Tobias, US, no. 1 (3 weeks)

- "Where the Blue of the Night (Meets the Gold of the Day)" (1931), with Roy Turk and Fred Ahlert, US, no. 4; US, 1940 re-recording, no. 27

- "I Don't Stand a Ghost of a Chance with You" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no. 5

- "My Woman" (1932), with Irving Wallman and Max Wartell

- "Love Me Tonight" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no. 4

- "Waltzing in a Dream" (1932), with Victor Young and Ned Washington, US, no.6

- "I Would If I Could But I Can't" (1933), with Mitchell Parish and Alan Grey

- "Where the Turf Meets the Surf" (1941)

- "Tenderfoot" (1953)

- "Domenica" (1961)

- "That's What Life is All About" (1975), with Ken Barnes, Peter Dacre, and Les Reed, US, AC chart, no. 35; UK, no. 41

- "Sail Away to Norway" (1977)

[edit] Filmography

[edit] Discography

[edit] Radio

- The Radio Singers (1931, CBS), sponsored by Warner Brothers, 6 nights a week, 15 minutes.

- The Cremo Singer (1931–1932, CBS), 6 nights a week, 15 minutes.

- Unsponsored (1932, CBS), initially 3 nights a week, then twice a week, 15 minutes.

- Chesterfield's Music that Satisfies (1933, CBS), broadcast two nights, 15 minutes.

- Bing Crosby Entertains for Woodbury Soap (1933–1935, CBS), weekly, 30 minutes.

- Kraft Music Hall (1935–1946, NBC), Thursday nights, 60 minutes until Jan. 1943, then 30 minutes.

- Armed Forces Radio (1941–1945; World War II).

- Philco Radio Time (1946–1949, ABC), 30 minutes weekly.

- The Bing Crosby Chesterfield Show (1949–1952, CBS), 30 minutes weekly.

- The Minute Maid Show (1949–1950, CBS), 15 minutes each weekday morning; Bing as disc jockey.

- The General Electric Show (1952–1954, CBS), 30 minutes weekly.

- The Bing Crosby Show (1954–1956, CBS), 15 minutes, 5 nights a week.

- A Christmas Sing with Bing (1955–1962, CBS, VOA and AFRS), 1 hour each year, sponsored by the Insurance Company of North America.

- The Ford Road Show (1957–1958, CBS), 5 minutes, 5 days a week.

- The Bing Crosby – Rosemary Clooney Show (1958–1962, CBS), 20 minutes, 5 mornings a week, with Rosemary Clooney.

[edit] RIAA certification

| Album | RIAA[46] |

|---|---|

| Merry Christmas | Gold |

| Bing sings | 2x platinum |

| White Christmas | 4x platinum |

[edit] References

- ^ a b Grudens, 2002, p. 236. "Bing was born on May 3, 1903. He always believed he was born on May 2, 1904."

- ^ Music Genre: Vocal music.Allmusic. Retrieved October 23, 2008.

- ^ Obituary Variety, October 19, 1977.

- ^ "Bing Crosby Billboard Biography". Billboard. http://www.billboard.com/artist/bing-crosby/3574#/artist/bing-crosby/bio/3574. Retrieved October 28, 2009.

- ^ Giddins, 2001, p. 8.

- ^ Gilliland, John. Pop Chronicles the 40's: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40's. ISBN 9781559351478. OCLC 31611854., cassette 1, side B.

- ^ Giddins, 2001, p. 6.

- ^ a b Hoffman, Dr. Frank. "Crooner". http://www.jeffosretromusic.com/bing.html. Retrieved December 29, 2006.

- ^ Cogan, Jim; Clark, William, Temples of sound : inside the great recording studios, San Francisco : Chronicle Books, 2003. ISBN 0811833941

- ^ "Lifetime Achievement Award. ''Past Recipients''". Grammy.com. February 8, 2009. http://www.grammy.com/Recording_Academy/Awards/Lifetime_Awards/. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Bing Crosby had no birth certificate and his birth date was unconfirmed until his childhood Roman Catholic church in Tacoma, Washington, released the baptismal record that revealed his date of birth.

- ^ {http://www.historylink.org/index.cfm?DisplayPage=output.cfm&file_id=7445}

- ^ {http://www.gonzaga.edu/Academics/Libraries/Foley-Library/Departments/Special-Collections/exhibitions/GonzagaHistory1980.asp}

- ^ Giddins, Gary (2001). Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams.

- ^ Giddins, 2001, p. 24.

- ^ Newkirk, Newton (14 March 1909). "The Bingville Bugle". http://www.spokesmanreview.com/blogs/history/media/bingville.pdf. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Newkirk, Newton (19 July 1914). "The Bingville Bugle". http://leonardodesa.interdinamica.net/comics/lds/bing/bingville.asp. Retrieved 25 September 2010.

- ^ Gary Giddins (8 October 2002). Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams - The Early Years, 1903 - 1940, Volume I. Back Bay Books. http://books.google.com/books?id=Oa2_zcwucAgC&pg=PA39&lpg=PA39&dq=bing+crosby+bingo+bingville+bugle&source=bl&ots=8DHK9U9Lfl&sig=BLFVQNnhQflUL769bVqYXepaWY8&hl=en&ei=JVqeTI-XM4H68Aa-2cAl&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CCcQ6AEwBDgK#v=onepage&q=bing%20crosby%20bingo%20bingville%20bugle&f=false.

- ^ Gilliland, John. Pop Chronicles the 40's: The Lively Story of Pop Music in the 40's. ISBN 9781559351478. OCLC 31611854., cassette 3, side B.

- ^ a b c d e f g h http://www.allmusic.com/cg/amg.dll?p=amg&sql=11:hifoxqw5ld6e~T1

- ^ "Bing Crosby, Singer". Radio Hall of Fame. http://www.radiohof.org/musicvariety/bingcrosby.html. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

- ^ Guinness Book of Records 2007: ISBN 1-904994-11-3

- ^ "Crosby Movies". Waynesthisandthat.com. http://www.waynesthisandthat.com/crosbymovies.html. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Top 10 lists.

- ^ Crosby Movies.

- ^ Pleasants, H. (1985). The Great American Popular Singers. Simon and Schuster.

- ^ "Johnny Bond – WMA Hall of Fame". Westernmusic.com. http://www.westernmusic.com/performers/hof-crosby.html. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ Hammar, Peter. Jack Mullin: The man and his machines. Journal of the Audio Engineering Society, 37 (6): 490–496, 498, 500, 502, 504, 506, 508, 510, 512; June 1989.

- ^ An afternoon with Jack Mullin. NTSC VHS tape, 1989 AES.

- ^ History of Magnetic tape, section: "Enter Bing Crosby" (WayBack Machine)

- ^ "Tape Recording Used by Filmless 'Camera'," New York Times, Nov. 12, 1951, p. 21. Eric D. Daniel, C. Denis Mee, and Mark H. Clark (eds.), Magnetic Recording: The First 100 Years, IEEE Press, 1998, p. 141. ISBN 0-07-041275-8

- ^ "Time Magazine Article". Time Magazine. August 3, 1953. http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,822904,00.html. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (2010-09-23). "In Bing Crosby's Wine Cellar, Vintage Baseball". The New York Times. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/09/24/sports/baseball/24crosby.html?_r=1&src=mv. Retrieved 2010-09-25.

- ^ a b c Giddins, 2001, p. 181.

- ^ Callahan, Tom (2003-05). "The Bing dynasty: on the 100th anniversary of Crosby's birth, we celebrate the granddaddy of celebrity golf". Golf Digest. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0HFI/is_5_54/ai_101967390. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ Grudens, 2002, p. 59.

- ^ a b http://www.people.com/people/archive/article/0,,20084544,00.html

- ^ "Philip Crosby, 69, Son of Bing Crosby". New York Times. January 20, 2004. http://query.nytimes.com/gst/fullpage.html?res=9A01E5D61439F933A15752C0A9629C8B63. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ Bamberger, Michael (June 9, 2008). "Sports Illustrated. Nathaniel Crosby". Golf.com. http://www.golf.com/golf/tours_news/article/0,28136,1812977,00.html. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "NAB Hall of Fame". National Association of Broadcasters. http://www.nab.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Awards7&CONTENTID=11047&TEMPLATE=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm. Retrieved May 3, 2008.[dead link]

- ^ "The Official Home of Bing Crosby". Bingcrosby.com. http://www.BingCrosby.com. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ^ Hope, Bob (1990). Don't Shoot, It's Only Me!. Random House Publishers.

- ^ Giddins, 2001, pp. 427–428.

- ^ "World Golf Hall of Fame Member Profile". Wgv.com. http://www.wgv.com/hof/member.php?member=1040. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

- ^ "About the Monterey Peninsula Foundation". http://www.attpbgolf.com/charities/about-mpf.php. Retrieved December 15, 2009.

- ^ "RIAA certification". Archived from the original on June 8, 2007. http://web.archive.org/web/20070608063448/http://www.riaa.com/gp/database/default.asp.

- Bibliography

- Giddins, Gary (2001). Bing Crosby: A Pocketful of Dreams – The Early Years, 1903–1940. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-88188-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=Oa2_zcwucAgC.

- Grudens, Richard (2002). Bing Crosby – Crooner of the Century. Celebrity Profiles Publishing Co.. ISBN 1575792486. http://books.google.com/books?id=Mkz_w-WYiMAC.

- Macfarlane, Malcolm. Bing Crosby – Day By Day. Scarecrow Press, 2001.

- Osterholm, J. Roger. Bing Crosby: A Bio-Bibliography. Greenwood Press, 1994.

- Prigozy, R. & Raubicheck, W., ed. Going My Way: Bing Crosby and American Culture. The Boydell Press, 2007.

[edit] External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Bing Crosby |

- Official Bing Crosby website

- Bing Crosby at the Internet Movie Database

- Bing Crosby at the TCM Movie Database

- Bing Crosby at the Internet Broadway Database

- Bing Crosby Collection at Gonzaga University

- Conference Bing Crosby (November 2002)

- Bing Crosby Article – by Dr. Frank Hoffmann

- BING magazine (a publication of the ICC)

- "Bing still matters" (2007) by Ted Nesi, The Sun Chronicle

- Bravo Bing! A Tribute to Bing Crosby

- Bob Hope: The Road to Bed in TimesOnline

- Bing Crosby Official 10" (78Rpm) Discography

- A Bing Crosby Session based discography

| ||

| ||