Psychochemical weapons

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to: navigation, search

The USA was highly interested in the military use of LSD

Psychochemical weapons, also known as drug weapons, are psychopharmacological agents used within the context of military aggression. They fall within the range of mid-spectrum agents, i.e. an intermediate range between chemical weapons and biological weapons. Drug weapons are typically considered as non-lethal weapons[1].

Contents

[hide]

- 1 Soviet Union

- 2 The Iraqi weapon

- 3 Moscow hostage crisis

- 4 Adapting pharmaceuticals

- 5 See also

- 6 Video links

- 7 References

[edit] Soviet Union

[edit] Cold War suspicions

Potential weapon: BZ

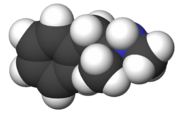

Potential weapon: LSD

In the early 1950s Western experts were convinced that the communists had already developed and used highly effective mind control and behavior-modification drugs. Public testimonies of US prisoners of war in Korea, or that of Cardinal Mindszenty of Hungary admitting to unrealistic crimes in fabricated trials appeared to support this conclusion [2]. And indeed, decades later Mindszenty mentioned pills that got him to make a confession [3]. Therefore, the CIA launched a project called MKULTRA to counter perceived Soviet and Chinese advances in brainwashing methods. A new branch of science, neuropharmacology, emerged in parallel with its immediate political and military use. The USA [4] and Britain were secretly working on the weaponization of LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) and BZ (3-quinuclidinyl benzilate) as nonlethal battlefield drug-weapons to develop psychochemicals for mind control in the battlefield [1].

However, evidence supporting the suspicions against communist regimes was scarce, and MKULTRA evolved into an offensive program. When accidentally uncovered, it involved about 150 research projects. The project was revealed by the US congressional Rockefeller Commission report. Details are not well understood since its records were deliberately destroyed. The British also concluded that the desired effects of drug weapons were unpredictable under battlefield conditions and gave up experimentation. Many experts in the East and the West equally suggested that drug weapon stories associated with the Soviet bloc were unreliable hints given the apparent absence of documentation in state archives [5].

[edit] Dissidents from the Soviet Bloc

General Jan Sejna defected to the United States after the brutal suppression of the Prague Spring by Warsaw Pact tanks in 1968. Formerly, he had been the head of the Defense Council Secretariat and Chief of Staff to the Minister of Defense in Czechoslovakia. He claimed to have been involved in planning and monitoring Czechoslovakia’s participation in drug warfare programs from 1956 [5]. He noted there had been two programs. The program code-named Peoples’ Friendship aimed at large-scale drug trafficking with the goal to harm western societies at their own expenses. Another program, code-named Flute was targeting the political and religious opponents within the homeland.

Ion Mihai Pacepa

A decade later, Lieutenant General Ion Mihai Pacepa defected to the USA. Ha had been the head of the Securitate (the secret police of communist Romania) – the highest-ranking intelligence officer ever to defect from the communist era. He also mentioned these two types of drug misuses [6] partially in collaboration with Cuba [7].

Finally, Kanatjan Alibekov (aka Ken Alibek), the 1st Deputy Chief of the Soviet Union’s (later Russia’s) illegal bioweapons program, defected in 1992. He mentions the project code-named Flute in his memoirs [8] as a major project aimed to develop psychotropic and behavior-modification drugs. He claims that this development took the form of a large-scale project pursued in major psychiatry clinics of Moscow.

These three defectors were knowledgeable high-ranked officers; however after their defections they earned money by selling their stories. This gave rise to skepticism about the reliability of their claims. Independent reports of former target persons verify the widespread misuse of psychoactive drugs in the psychiatry clinics of the Warsaw Pact. However, they refer to drug misuse in a medical sense, while direct military aspects were not known up to recently [9][10]. Thus, contrary to widespread rumors, there was little, if any, evidence to support the view that the Soviet Union or its satellite states considered drug weapons in a militarily context.

[edit] Recent findings from the former Soviet Bloc

Methylamphetamine: a potent "truth drug"?

This view has changed recently, when the Hungarian State Archives opened up declassified records of Hungary’s State Defense Council meetings (1962–78) [11]. These include documents describing the coordinative meetings of the Warsaw Pact military medical services. Research into possible countermeasures against psychotropic drugs is listed as a research priority assigned to Hungary in 1962. Hungary rejected this task in 1963, but joined the ongoing project again in 1965. Methylamphetamine was produced in Budapest for use as an experimental model. Contemporary Western experts considered this drug as an interrogation tool, so-called truth-drug. Similarly to contemporary CIA, Hungary also failed to develop an antidote and the Hungarian project was terminated fruitlessly in 1972. In fact, these documents serve as evidence that a Warsaw Pact forum had considered a psychochemical agent as a weapon [11].

[edit] The Iraqi weapon

The existence of a BZ-related compound, called Agent-15, in Iraq's arsenals was revealed in 1998. Apparently, Iraq possessed large quantities of the agent since the 1980s. A document found by the United Nations Special Commission (UNSCOM) in 1995 contained a brief reference to this agent and subsequent assessment of relevant scientific and other background material indicated the size of the stockpile. [12]

[edit] Moscow hostage crisis

Main article: Moscow hostage crisis chemical agent

In October 2002, Russian Spetsnaz (special forces) pumped an unknown agent into a theatre being held by Chechen rebels, subduing them, but also causing fatalities among the hostages.

[edit] Adapting pharmaceuticals

British researcher Malcolm Dando has warned of the potential for military adaptation of legal pharmaceuticals to military purposes. He has called for the strengthening of the Chemical Weapons Convention to outlaw this technique.[13]

[edit] See also

[edit] Video links

- British military LSD test

- Czechoslovakian military LSD test

- American military LSD test

- CIA, MKULTRA: mind control experiments

[edit] References

- ^ a b Dando M, Furmanski M 2006. Mid-spectrum incapacitant programs. In: Wheelis M et al. (eds). Deadly cultures: the history of biological weapons since 1945. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

- ^ Douglass JD 2001. Influencing behavior and mental processing in covert operations. Medical Sentinel, 6, 130-136.

- ^ Mindszenty J 1974. Memories [in Hungarian]. Toronto: Vörösváry.

- ^ Szinicz L 2005. History of chemical and biological warfare agents. Toxicology, 214, 167-181. accessed: 30. 03. 2009.

- ^ a b Douglass JD 1999. Red cocaine – the drugging of America and the west. London and New York: Edward Harle Limited.

- ^ Pacepa IM 1993. The Kremlin Legacy [in Romanian]. Bucharest: Editura Venus.

- ^ Pacepa IM 2006. Who is Raul Castro? A tyrant only a brother could love. National Review Online, August 10. accessed: 30. 03. 2009.

- ^ Alibek K, Handelman S 1999. Biohazard: The chilling true story of the largest covert biological weapons program in the world — told from inside by the man who ran it. New York: Random House.

- ^ Rózsa L, Nixdorff K 2006. Biological weapons in non-Soviet Warsaw Pact countries. In: Wheelis M et al. (eds.) Deadly cultures: the history of biological weapons since 1945. Cambridge, US: Harvard University Press.

- ^ López-Munoz F et al. 2006. Psychiatry and political-institutional abuse from the historical perspective: the ethical lessons of the Nuremberg Trial on their 60th anniversary. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry, 31, 791–806. accessed: 30. 03. 2009.

- ^ a b Rózsa L 2009. A psychochemical weapon considered by the Warsaw Pact: a research note. Substance Use & Misuse, 44, 172-178. accessed: 30. 03. 2009.

- ^ Zanders JP: CW Agent Factsheet - Agent-15 accessed: 30. 03. 2009

- ^ writing in Nature, and quoted at [1], 19 Aug 2009.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychochemical_weapons"

Categories: Psychiatry | Political abuses of psychiatry | Biological warfare | Bioethics | Less-lethal weapons | Incapacitating agents | Mind control